By Professor Savitri Goonesekere

Professor Savitri Goonesekere, Emeritus Professor of Law and part of the Government delegation at the Fourth World Conference on Women in Beijing. Professor Goonesekere was the first woman Vice-Chancellor at the University of Colombo (1999 - 2002). She is a graduate from the University of Ceylon and was the first woman lecturer at the University of Ceylon, Department of Law and the first woman Professor of Law at the University of Colombo.

"Celebrating 30 years of adoption of the Beijing Platform For Action (BPFA) 1995 has been an opportunity for me to reflect not just on a personal journey, but past experiences on the impact of a women's human rights approach to a gender equality agenda, its successes and failures."

My professional experience, embedded in that approach, and reflected in the BPFA, has brought for me great personal and career fulfillment. Yet the post BPFA years, nationally, regionally and internationally, have also brought with them a sense of deep disappointment. For I have had to witness the dilution of this lens and our incapacity to sustain and develop it as we should have, in our work to achieve a gender equality agenda.

"A new generation of researchers activists women's groups and international and national officials may not be familiar with the manner in which the BPFA (1995) became a pathbreaking link to the UN CEDAW treaty (1979)..."

So that all governments and non governmentals were required to adopt a women’s rights-based approach in their work on gender equality. In 1995 CEDAW had not been ratified by most governments. The approach to gender equality was embedded in a women in development (WID) approach that ignored the women’s human rights perspective on achieving gender equality.

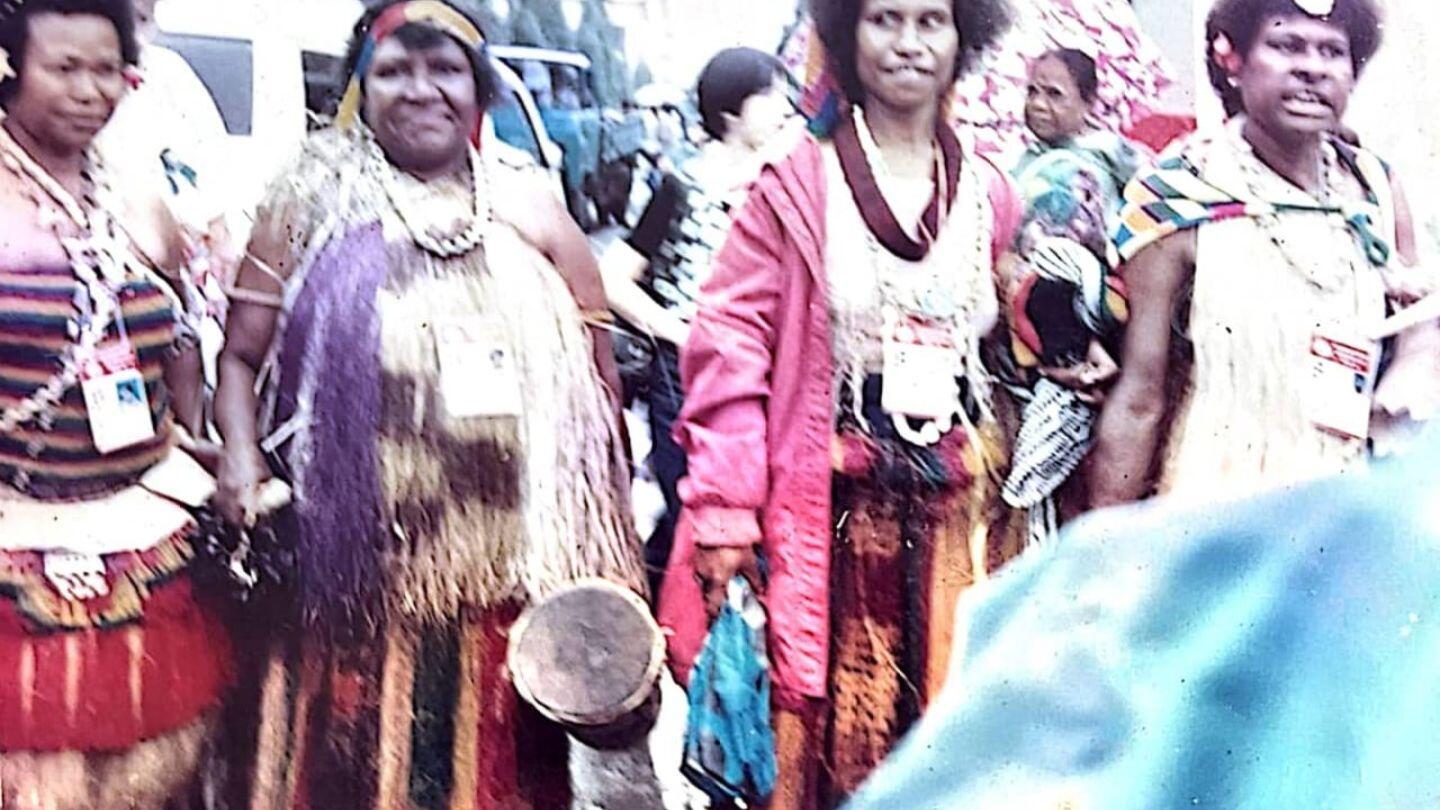

When we women participated in the Beijing conference, a gender architecture in Sri Lanka, a Women's Ministry had been established. Researchers and activists and women's groups had used this opportunity to bring to the official gender architecture the need to bring a "Human Rights of Women" lens to gender equality. The government adopted a policy document called the Women's Charter in 1993, which also provided for a National Committee on Women (NCW) to implement the Charter. The delegation to the Beijing Conference consisted of members from the NCW, its Chair and Executive Director. Amazingly all of whom were from Non-governmental Organisations and women's groups working on gender issues. It was the BPFA that forged that close connectivity between the gender equality agenda of governments, Non-governmental Women's Groups and activists.

"The BPFA integrated the wisdom of the Vienna World conference 1993 in its content, and also specifically asked governments to ratify CEDAW."

Ratifications increased rapidly, and very soon the CEDAW was a treaty ratified by ALL countries of our own region South Asia. The Expert Committee of CEDAW on which I was privileged to be elected and serve from 1999 to 2002 asks for progress on BPFA in their progress reviews of State Party Reports. Hence, CEDAW implementation and BPFA governments commitments became complementary and parallel rather than conflicting agendas. This post Beijing environment catalysed significant dynamism within State agencies with committed and professional government officials who wanted to carry forward the BPFA and CEDAW agenda, networking closely with Non-governmental Women’s groups researchers and gender activists. The legal reforms from 1995 to 2005, the institutional strengthening and programming interventions to implement the gender equality agenda in this period, indicate that these were indeed successes of the time.

UN and International agencies partnered with both the State and the Non-governmental agencies in networking and interaction that was not suspect or considered adversarial by official state agencies. Perhaps the gap was in the inadequate resource allocation and the incapacity to advocate for progress and monitor the limitations in enforcement. This became most apparent in regard to commitments on responding to gender based violence and women's economic participation.

"The manner in which the government responded promptly to CEDAW Concluding Observations and the BPFA commitments after a progress Review in 2002, demonstrates that the human rights lens strengthened the capacity to work together on the gender equality agenda."

The research and evidence base on social and economic realities was captured in regular BPFA and CEDAW reviews including development of indicators to monitor progress. These publications provide a wealth of often ignored women's human rights insights in responding to our current realities.

My own work as a researcher on women's human rights linked me with the work of women's groups, government and UN agencies. That also gave me access to sit at the "top table," and impact on law and policy reform. These were dark times in the midst of the horror of death and destruction in thirty years of armed conflict. Yet we came together in government institutions and a gender architecture that functioned, and women's groups that worked together on issues of common concern, including gender based violence in the conflict areas. We survived, fulfilled our official responsibilities, and lobbied successfully for some government interventions, and were heard. It was the solidarity and connectivity across ethnicity, race, religion and politics that helped many of us to survive, and also get career and personal fulfillment in the little spaces we had for our work on gender equality.

"All this changed with the end of the war. We won the war but not the peace."

Increasing rejection of a human rights agenda and international connectivity and lack of political will undermined BFPA and CEDAW commitments. The dilution of the gender architecture continued. Women's groups lost their capacity to work together with a common human rights approach to gender equality.

The political environment had a chilling impact and the post war years, ironically also creating divisions of race and religion even among women’s groups. I sustained my interest in the gender equality agenda as a personal endeavour, but without the satisfaction of witnessing the transformation and positive change, I wanted.

"The current Beijing +30 discussions, and the Concluding Observations of the CEDAW Committee demonstrate so clearly the stagnation and even regression on the gender equality agenda achievements, in the early years of this millennium."

It is ironical that the current global environment undermining human rights and democracy as a form of governance, and the International institutions, and the challenges of authoritarian governance replicates Sri Lanka's own history in the post war years. Yet our small island has now articulated a collective voice for accountable governance based on a "system change" that will respect and fulfill commitments on democratic governance and human rights.

"Let us hope that women in current political leadership who have assumed these responsibilities, and have the capacity to deliver on these promises, women's groups and activists and UN agencies work within solidarity and partnership."

They have an opportunity to bring that important BPFA-CEDAW human rights lens into the gender equality agenda.

To use a cliche, we may be able to light a small candle in our country, in these dark times, renewing faith in the value of liberal democracy as a form of governance, and a women's human rights based gender equality agenda.